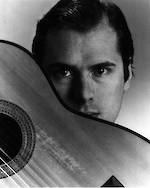

More on the Late Joel Suben

Joel Suben introduces Suite of Dances--

Joel Suben's "Where All the Waters Meet" at Kennedy Center--

In brief: "Suite of Dances" keeps to a more homegeous sound; "Where All the Waters Meet" seeks things that stand out and distinguish themelves as section-scale contrasts.

That more homogeneous --

The guitarists are so lucky to have Suben's "Suite of Dances". I always wished I could play Schoenberg op. 27. Now we can, but you need 2 guitars tuned a 1/2 apart.

Joel Suben's Suite of Dances was written in 1987, perhaps into 1988. He said one can trick to ear into hearing the impression of diatonic music. He was thinking of what Schoenberg does so wonderfully in op. 29, wherein one movement is a folksong setting.

This suggests to me that Suben's "straight 12-tone sound" was an homage to Schoenberg's neo-Baroque. What do I mean by "straight 12-tone sound"? For the moment, I'll just say that it lacks the foregrounding harmonies we hear in Suben's guitar solo, "Where All the Waters Meet", which is broadly comparable to schoneberg op. 9.

Since working with suben, I worked with Boykan, Suben's teacher at Brandeis, and discovered through Boykan's "Diptych" for Cygnus (see below), that Boykan is a master of what I call the (Schoenberg) op. 9 modality.

What do I mean by "straight 12-tone"? It may not be a good way to describe it. It's the sound of an agregate comprised of 6 on 6, which is what Schoenberg does so often. And it is fascinating to be in a space where the aggregate is so palpable. Even more palpable is the 5\2 1\2 aggregate of Schoenberg op. 27 #4, where every chord change is an agreegate, transparently. There, he breaks the homogeneity with the dominant 9 chord (no 5th) at the end. "Where All the Waters Meet" is not committed to aggregation in such a regular baked-in manner, and this allows the compositional flexibility to design large scale phenomena such as when we experience in Schoenberg op. 9. Interesting that Schoenberg did that first, then movened on, while Suben and others discoved those modalities in reverse order.

Babbitt's arrays and superarrays first expand the range of partitions (which tends to vary aggregate speed), then sets arrays in counterpoint (which compounds the aggregates and slows them down considerably. In superarrays something like what Suben & Boykan do can happen, but in very specific ways.

Where all the Waters Meet (WATWM) was written only a year or two after Suite of Dance. What Suben does in WATWM is most likely something he knew how to do when he wrote Suite of Dances. We must look at other works around this time. And so I might surmise that Suben was paying homage to Schoenberg's *6 on 6* 12-tone sound. Suite of Dances is basically 6 on 6, a diatonic hexachord in counterpoint with its complement, like the opening of Wuorinen's Sonata for Guitar and Piano.....

A modernist American quest shared by Carter, Babbitt, Boykan, and clearly Suben, was something less homogeneous. The homogeneity was useful as a way to float between things. Between what things? The things that leap out and grab you. Oddly, this is done very well in Schoenberg's op. 9, where everything revolves around the section with the 4ths.

Think of Suben's C#, B, E harmony as the thing that anchors like Schoenberg's fourths in op. 29.

The opening of WATWM begins with C#, B, E harmony that is striking for the scordatura tuning of the sixth string dow a minor third to C#.

I propose that it's hard to miss the return of that opening harmony in m. 16, and there are some reminders in m. 8 -- a phrase ending with the E in that same register. (See last bit about this on the RSF site.)

Isn't it hard to miss these perfet consonances a major third apart?

And in the middle sections, we get fourths a tritone apart, but delivered as tritones a fourth apart?

Hard to miss --

Joel remarked that the fifth a tritone apart is something much loved by Schoenberg. But Boykan & Suben were finding ways to deliver things that stand out, with a rich palette of greys to transport to the next thing that stands out, an escalation. The fourths a major third apart (major 7 chords) stand out, and m. 162 jumps to the fore stronger still.

The passage in and out of 162 I find rare and beautiful.

Boykan's Diptych (2013) for comparison. We must examine Boykan's work from the late 80s to compare with WATWM.