Simple Composition

Charles Wuorinen's book *Simple Composition* tells us what made him tick when he wrote it. He was brave to put his cards on the table. In his book he declared his conscious intentions. He could not have told us his unconscious intentions. It's truly rare and wonderful to see that his later work shows such a meaningful and musically potent enlargement of his conscious musical concerns.

In the book he spoke of nesting. In order to nest at various time scales, one must instate focal pitches. See his Sonata for Guitar and Piano for great examples.

From the end of section two into the beginning of section 3, D, the guitar's open (4) string is a focal pitch. It ties together the two sections. The 2nd section ends with pitches beautifully revolving around that pitch. The last section begins with a fast tempo and fresh energy, still keeping that pitch in play. The last section ends with that same D in a bluesey E7 chord, which the 7th being that open (4) string.

He told me D is the *0* of the piece.

The problem with this orientation is that focal pitches help hold things together, but they do not reliably get manage harmonies such that they their teeth into you. The E7 chord that ends the piece could get its teeth into you. A harmony, treated as a point of departure and return can get its teeth into you. But there are no other dominant 7 chords in the piece. It's just a little gag at the end.

Focal harmonies stick with us. They can have enormous range, which is to say that we can remember a harmony/tune over long spans of time. For example, we remember 4ths from the opening of Schoenberg op. 9 all the way to the middle section that brings back the stacked 4ths. Focal pitches hold sway over shorter time spans because they hold less punch, they have a shorter range. Focal pitches are foreground glue. Focal pitches can start to grow a middle ground, but not a bigger middle ground or a background.

In his book Wuorinen mentions the circle of 5ths transform without giving us a clear idea about how it helps us musically, viscerally, palpably. But in his later work he wields that transformation powerfully, projecting focal tetrachords through the piece.

He told me around the time he wrote *Cygnus *and *Electric Quartet* that he achieved a reorientation from row to tetrachord. In his sextet, *Cygnus*, the chromatic tetrachord is memorable. It will get its teeth into you if you let it.

If you land a chromatic tetrachord, leave it and return to it, you have made a magic circle. You make a phrase that is comparable to a classical phrase. In many ways it is more rich than the classical phrase. In many classical phrases this game is already seen at play. 6/4 chords and other appoggiaturas help make phrase endings memorable. Mozart's sharp 9 moves grab you by the lapels and rub your nose in the phrase ending, over-forgrounding even the V7 and the 6/4.

Prolonging the chromatic tetrachord is still a middle-ground thing. On a larger time scale, what Wuorinen does in *Cygnus* is aim for the M5 mod12, the circle of 5ths transform of the chromatic tetrachord. In *Cygnus* your ears are rewarded with a full frontal diatonic tetrachord. It arrives as the grand climax of the story of the transformation of the chromatic tetrachord.

That has more range than the game of focal pitches. The focal pitch game may play into the focal harmony game. They can work nicely together.

Before Wuorinen achieved the pivot that I'm trying to describe, his music left some things to instinct, remaining outside of his conscious control. I argue that the pivot shifted his attention in a good way.

In both US post-minimalism and the EU spectral orientation I see the same problems that Wuorinen corrected. Something compelled Wuorinen to shift his attention in a way that I hear and appreciate, but the minimalists and the spectralists appear to be entrenched.

Marty Boykan, in conversations and in his book, used the most plain language to suggest to me what he hoped to impart to his students. He said he focused on "some things to do with phrases." I like that. What I'm describing is to do with phrases -- instate (a focal harmony/tune) lift-off, landing back in the focal harmony.

instate -- liftoff (float through the midphrase) -- land back in the harmony/tune, etc.

But the landing places can evolve. That's very neoclassical, but because we're not using triads but trichords or tetrachords or in the case of Schoenberg, Babbitt, Awad -- hexachords, there's little danger of sounding too neoclassical. Boulez found Schoenberg too neoclassical, favoring Webern. But for me, Webern is still neoclassical enough. He doesn't throw away the baby with the bathwater.

Wuorinen's way is rhythmically involved with his nesting, avoiding any reminiscence of the classical phrase.

Alex Lipowski explained to me that Davidovsky and Wuorinen were not cool enough for Klangforum Wien. I've come to suspect that the very concerns that we see in both early and late Wuorinen are precisely what makes their music feel out of fashion now in Vienna.

Rather than unsubscribing from Vienna, I'll say to Vienna what I had come to say about early Wuorinen -- one's conscious focus is always lacking something, and one's unconscious can always come to the rescue. Alex & Klangforum Wien are asking us to wait for them to hit it by instinct. My fallible theory of mind keeps telling me there is an allergy in Vienna to all the makes music potent for me. I sense entrenchment.

And nevertheless I will concede that the situation of the Klangforum Wien values is similar to that of the Wuorinen of Simple Composition. While the KW people are proud of things that prevent their music from working in a way that makes me happy, it's perfectly reasonable to expect that their instincts can take them out of their trenches to do something that doesn't annoy me, despite themselves. I'm being as horribly pissy as the Wuorinen detractors. I am celebrating those detractors.

I love much of that earlier Wuorinen, but I also slowly began to object to what Wuorinen himself must have objected to, motivating his pivot. And I do not listen in a vacuum. I gave ear to Wuorinen bashers. My initiation to Wuorinen was through the clearly sincere and ardent enthusiasm I got from Raymond DesRoches. My guitar mentor David Starobin was also a Wuorinen fan. We fall into composer circles. I fell in with the Wuorinen people, but I got an earful from the Wurorinen detractors. What's really wonderful and surprising is that Wuorinen answered his detractors substantially. He pivoted at almost exactly the same time that I capitulated to his detractors. That is funny.

You're Wuorinen and you're nesting. You're telling a nesting story, perhaps subsets of the rows offer something (some internal break) that feels like a revelation and it coincides with a move from one nested pitch to another. That would give the moment some harmonic punch. What Wuorinen did so very well in his earlier music was to mark a big moment in his nesting scheme with rhythmic sizzle. He embraced physical Stravinskyian rhythms to generate excitement about the bigger moments in his nesting schemes.

Counterpoint: when you combine rhythmic sizzle with a meaningful harmonic break (a break out of or into a symmetry, for example) the moment has greater depth. Get used to that counterpoint, that overdetermination, and soon one feels that rhythmic sizzle without harmonic contrast is a depraved condition. Having lived more deeply, the underdetermined starts to feel like an empty gesture. Wuorinen was inspired at times, bringing him to potencies that his conscious orientation had not brought to light. He found his way to more potent gestures and gradually got the knack for such potencies and pivoted to a new conscious focus.

*Simple Composition* tacitly declared the inattentions that Wuorinen corrected later. The most egregious result of such inattention is a sense of empty gesture. Wuorinen could have rested on his entitlement, his Pulitzer, his loyal performers like me and Ray, but he did not.

I'll leave it there for the moment.

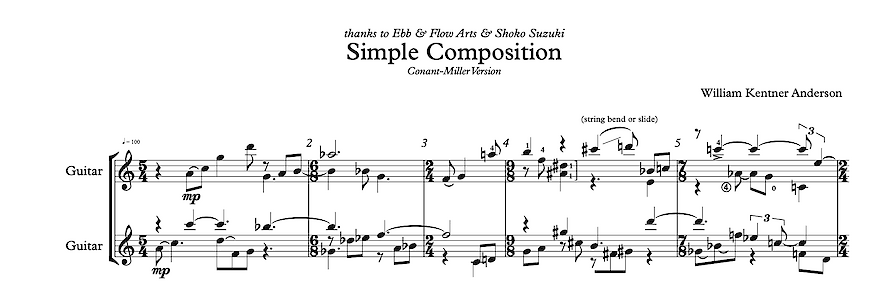

My little duo, "Simple Composition" is based on an ostinato composed by Shoko Suzuki's students at a Japanese weekend school in New Jersey. It is shows my understanding of what a phrase is. It developed over many years and got another major revision a few days ago. So grateful to Kyle Miller and Daniel Conant for taking it on. The Wuorinen pivot is in evidence, but more recently I noticed that my yearning for the meaningful relationships seen in Bach's binary forms is coming into focus. I lost interest for a time because I had an ideological quandry. The ostinato modulates by a tritone. A tritone modulation is not a modulation at all. It's merely a weighting on the complement of a diatonic hexachord. That complement is there in the middle bar of the first two three-bar phrases.

When I thought of the little piece in this way, I ceased objecting to this weighting of the complementary diatonic hexachord --